Think about a popular influencer you know. They could be any kind of influencer - fashion, politics, literary, travel - anything. When you go to their social media profile, you will see their topic of choice reflected in every aspect of it, right?

Their bio will contain statements and links that serve as social proof of their topical expertise. Their pinned posts will be their most popular pieces of content. Their posts will all be about that one topic. In fact, many influencers refrain from posting about anything other than the topic that they have come to be associated with. It has to do with the nature of social networks, which reward topicality and punish deviations from what the algorithm has come to associate with you.

So powerful is the hold these patterns have over us that people literally start fresh accounts to talk about a hobby of theirs or to share personal pictures and videos. To do so on their 'main' - the account devoted to the topic they are known for - would amount to social media seppuku. A human being is complex and capable of change. The reason their social media profile cannot accurately represent them is because it calcifies into something unnaturally solid. The person behind the profile, for the sake of acceptability, has to continue to pretend that they too are only one thing, unchanging and immutable.

I have been there, and I have even written a personal essay about the problem of becoming prisoner to your own online identity.

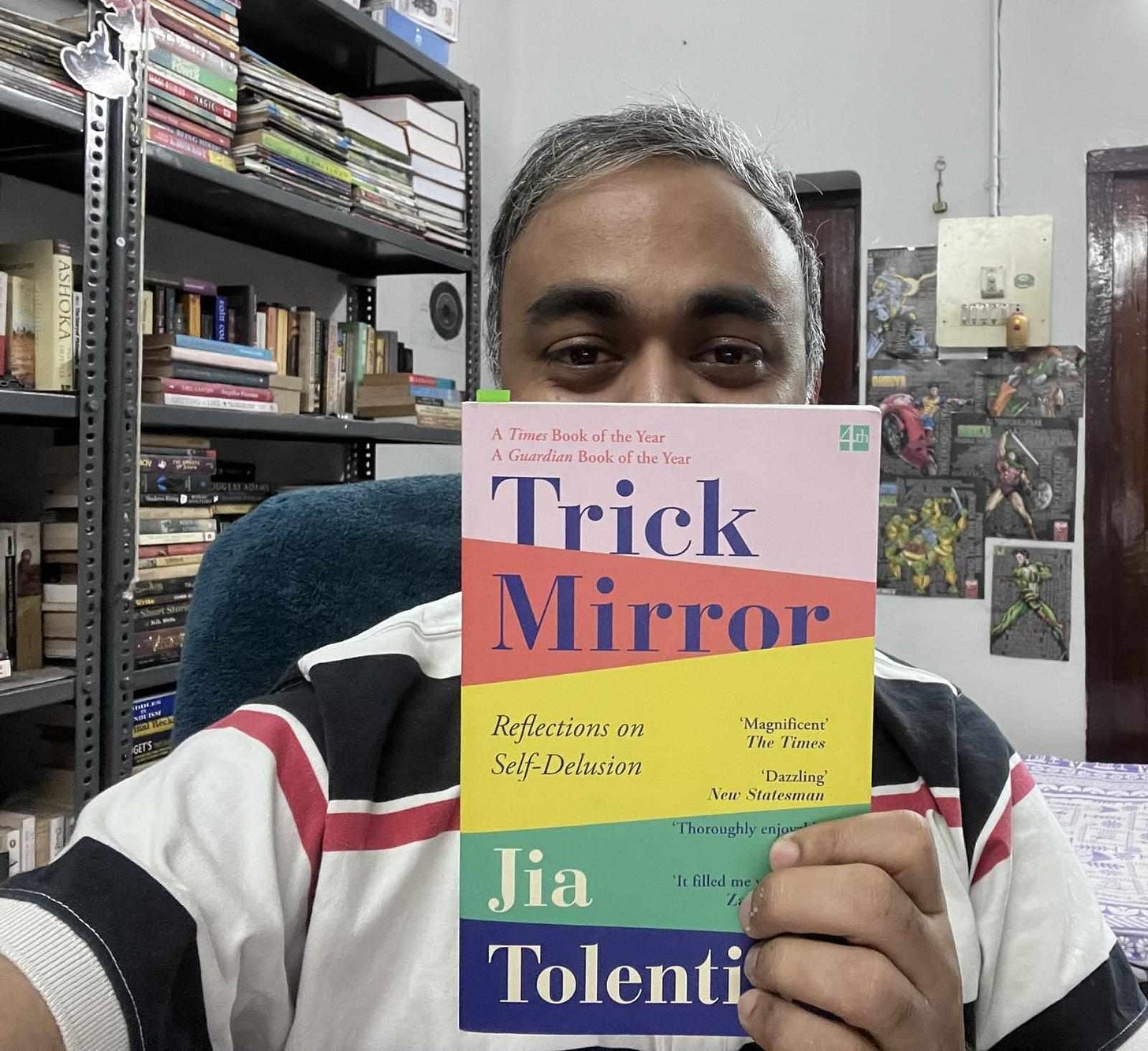

I was reading Jia Tolentino's book Trick Mirror recently and found this in the chapter titled The I in the Internet.

On social media platforms, everything we see corresponds to our conscious choices and algorithmically guided preferences, and all news and culture and interpersonal interactions are filtered through the home base of the profile. The everyday madness perpetuated by the internet is the madness of this architecture, which positions personal identity as the center of the universe. It’s as if we’ve been placed on a lookout that oversees the entire world and given a pair of binoculars that makes everything look like our own reflection. Through social media, many people have quickly come to view all new information as a sort of direct commentary on who they are.

Tolentino's book, which is highly recommended by the way, talks at length in this chapter about how we are all performing on the Internet. We are all - influencer or not - only too acutely aware of what we look like and what is expected of us by those who follow us. Our identity becomes the great filter through which all else flows before washing upon the shores of our aesthetically-curated social media profiles.

Recently, there was chatter about whether TikTok is ruining books and the same pattern became apparent there as well. People are buying books and not reading them because the driving force behind booktok is not reading. It's looking like a reader. Like this GQ article says:

Or the dude who says that one of his tips for learning to read more is to “romanticise reading” by finding a cute outfit to read in. Or the person who has made miniature versions of every book they read in 2022 and displays them in a frame. Or the person who has “re-tabbed” their books because the tabs stick out too much and they want the colour match the tabs to the books’ covers. With all of this effort being put into being seen as a reader, one wonders how any of them have the time to read.

I don't know about you, but reading is chaotic for me. It's about dog-eared pages, overflowing shelves, scribbles in bad handwriting in the margins of pages. I suppose that too is an aesthetic. But it is not a cultivated one. It grows out of the hurry and flurry of life itself, like weed.

How many of your favourite influencers are prisoners of your expectations? How many of them are interested in appearing to be who they seem to be rather than being who they are expected to be? And here is an even more interesting question - how many of them are not who they appear to be and are only putting up the pretense because there is profit and / or social currency in being who they are pretending to be?

And the troubling part is, this doesn't apply only to them. It applies to you and I as well. We are all married to our image online because the online economy, based on attention and approval, coalesces our incredible complexity into neat little, easily-digestible identities for the benefit of advertisers. Algorithms put us in folders and generalise the living daylights out of who we are. And in order to survive in this algorithmic reality, we are all trying to adapt to the lowest common denominator of expectations.

This isn't really a new problem. I wrote in 2020, somewhat more angrily (for obvious reasons), about how many in the Indian savarna middle class value the appearance of something more than the thing itself.

Though the two behaviours are essentially the same, they are motivated by different forces. The cultural commitment to appearances that I referred to in my 2020 essay is driven by the need for social dignity. In thousands of small towns across India, your neighbours (perhaps the parents of the girl you want to marry) don't care if you are good at your job as an engineer. They only care that you are called one and that you get paid as much as one and that you get treated as one. The same goes for every 'reputable' profession. Reputation is the currency of the social market that we all shop in.

Online, your social media reputation is often a stand-in for actual currency. You need to appear to be what the algorithm or your fans think you are because your earnings depend on it. But even when a content creator's account or channel isn't monetised, a significant part of their ability to feed themselves and their business depends on their reputation. The advertiser who sends them things to promote needs to be sure if they are visibly about what they say they are about.

While once our audience was our immediate neighbourhood, now it has expanded into a wider world accessible through the little devices in our pockets. Our follower base is potentially the entire planet and the people who we need approval from are our more spread out than before. Where once we received safety and dignity from the invisible 'likes' of our mohalla and town, we now rely on those same metrics made tangible through a digital interface.

It has never been particularly hard to become part of a tribe or even a particular identity by appropriating its markers. Anyone can claim to represent a religion by merely looking like they belong to it. Anyone can claim to be a scholar by putting on the appearance of what people think scholars look like. Anyone can play-act their way into a tribe by appropriating uniforms, slogans, and gestures. Social media is full of such instances. At its core however, is not some new phenomenon invented on the social web. At its core is familiar old unforgiving human tribalism.